Since the enforcement of the Act on Special Measures Concerning the Procurement of Electricity from Renewable Energy Sources by Electricity Utilities (the FIT Act) in 2012, renewable energy, especially solar power, has expanded rapidly. The Institute for Sustainable Energy Policies (ISEP) estimates that Japan’s renewable energy power generation ratio, which was 10.1% in 2012 and increased to 15.6% in 2017, with 5.7% of the increase being attributed to solar power.

Since the enforcement of the FIT Act, large-scale solar power generation (mega-solar) exceeding 100 kW (= 1 MW) has expanded significantly. From the enforcement of the FIT Act to the end of December 2007, 5,895 cases, 13,370 million kW of the mega-solar power plants were introduced throughout Japan. This is equivalent to one-third of the increase in solar power generation over the same period.

With the rise in solar power generation, conflicts with local governments and local residents have increased. Accidents caused by disasters after the completion of the equipment have also been reported, but as no consensus was reached between the business operator and residents, various groups and the administration at the business development and operation stages state that there were a number of incidents with the movements of local residents and guidance from the administration.

In the following, this article examines these regional conflicts and derives lessons for the government, businesses, and resident groups.

Overview of solar-related local conflicts

Local conflicts in the media

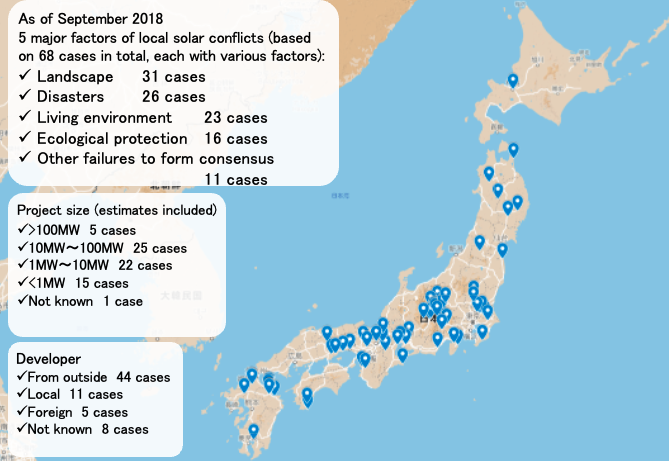

According to a survey by ISEP based on information from the mass media, such as newspapers published in March 2016, 50 conflicts were confirmed relating to solar development, in particular landscape, disaster prevention, conservation of the living environment, and nature conservation. As ISEP’s investigation proceeded, by August 2008, the number of similar confirmed cases was 68 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Local conflicts caused by solar power generation (created with Google Map)

By prefecture, the number of cases is high in Nagano prefecture (10 cases), Oita prefecture (7 cases), and Yamanashi prefecture (6 cases). There are 52 conflicts for a range of mega-solar power plants with a scale exceeding 1 MW, and 5 of them are over 100 MW.

On the other hand, 15 conflicts have occurred even on a scale of less than 1 MW. However, the number of actual local conflicts is considered to be higher than what had been reported in the media.

From the perspective of a nationwide municipal government survey

From the “2nd National Survey of Renewable Energy in Municipalities” conducted jointly with Hitotsubashi University from May to July 2007, regional conflicts related to renewable energy in local governments became clear.

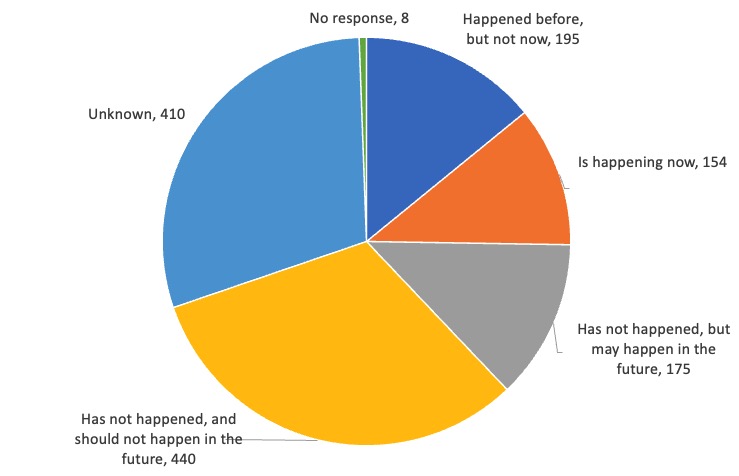

Figure 2 shows the answer to the question, “Are there any complaints or conflicts from local residents regarding the renewable energy facilities in your local government?” More than a quarter of the respondents said that such conflicts had occurred in the past or they are occurring now.

Furthermore, compared to the first survey in 2014, the ratio has increased by about 2.5 times. Considering the rate of increase in renewable energy facilities during this period, it is considered that conflicts related to photovoltaic power generation are increasing.

Moreover, the 524 local governments who answered that the conflict had occurred in the past, it is occurring now, or they are concerned about the occurrence remarked that the specific details of the conflict are the scenery (275 local governments, 52.5%), light pollution (185 local governments, 35.3%), noise pollution (161 local governments, 30.7%), sediment-related disasters (137 local governments, 26.1%), and the deterioration of the living environment (133 local governments, 25.4%). There were multiple answers, including those who were concerned about the occurrence of specific matters.

Noise pollution is considered to be strongly related to wind power generation, but all others also apply to solar power generation.

Fig. 2 Complaints and conflicts against renewable energy facilities (by the 2nd National Survey of Renewable Energy in Municipalities)

Overview of the systems of national and local government

Since the revised FIT Act came into effect in April 2007, the important items that affect the prevention of local conflicts are (1) “obligation to comply with laws and ordinances” and (2) “recommendation of appropriate communication with local residents” (along with the business guidelines).

Because of (1), the prevention of regional conflicts is anticipated. If the local government establishes appropriate ordinances, it will lead to cancellation of an authorized business plan if there is a violation of the ordinance. (2) is just a recommendation, and there is no stipulation on what to do if proper communication is not performed.

Currently, the national environmental impact assessment system does not cover solar power generation. Although studies will begin to target it in the future, only large-scale plants of several dozens of MW will be covered in any case. It is important to note that this is a system for reducing the impact on the environment, not a system for forming an agreement with local residents.

From a broader perspective, the root of the regional conflicts is the issue of land development regulations in Japan. This issue has been repeatedly caused by the development of other projects such as resorts and golf courses in the past.

For example, the development of agricultural land is heavily restricted by the Agricultural Land Law, but the development of forest land is relatively easy. As a result, a large-scale development plan for forest land has been compiled and concerns about landscapes, sediment-related disasters, and flood damage have increased.

Within such a national policy framework, local governments facing regional conflicts mainly deal with a combination of five types of institutional measures. (1) Suppression by new ordinance, (2) Utilization of residents’ agreement by existing ordinance, (3) Application of environmental assessment ordinances, (4) Procedural obligations by ordinances and guidelines, and (5) Administrative guidance.

(1) defines the area where the installation of solar power generation is restricted or enacts an ordinance that requires notification and consent to the mayor.

(2) states that if there is a provision in the existing landscape ordinance or nature conservation ordinance that requires the consent of the local residents during development, the provision will be used.

(3) most of the prefectural environmental assessment ordinances target large-scale solar power generation where the impact of disasters and nature conservation will be reduced through deliberation.

(4) is a procedural method that requires notification and briefing sessions with residents in advance, even for small and medium-sized solar power generation projects by enacting ordinances and guidelines.

(5) the local government will provide administrative guidance such as reducing the impact of development through agreements and negotiations with businesses, taking alternative measures, and encouraging the formation of respectful consensus with residents.

Since the institutional response of local governments, the response of businesses, and the movement of residents influence the whereabouts of regional conflicts, we will look at specific cases in the next section (See also Maruyama’s paper on this special issue on regional consensus building).

Specific examples and lessons derived

Regional conflicts across Suwa City and Chino City

A plan for operator A from Tokyo to set up a solar power generation business of 89 MW on the land managed by the Makino Association in Suwa City, Nagano Prefecture, was reported in a newspaper in February 2015.

In response to this plan, a group of residents in the downstream area of Chino City has requested that the plan be canceled because of the landslide disaster which occurred in the past on the river that continues from the swamp on the premises, concerns about the impact on spring water, valuable plants found at the planned site, and the existence of wetlands.

A residents’ group has submitted a petition and signatures to the Chino city council, and the city council has resolved to adopt the petition. The residents’ group has also submitted requests and signatures to the mayors of Suwa and Chino. In addition, the surrounding fisheries cooperatives have expressed concerns.

In this case, the photovoltaic power generation business was the first to be subjected to the Environmental Assessment Ordinance in Nagano Prefecture, and the prefecture has given opinions on many items through the scoping document procedure.

As of the end of August 2008, it was in the preparatory stage, and the business operator changed the plan in response to the advice of the prefecture and is advancing with the procedure.

The Environmental Assessment Ordinance itself is not a system for stopping business in the first place. However, the mayor’s opinion is widespread, and attention is being paid to how businesses respond. There are two lessons derived from this case.

The first is the difficulty of dealing with local governments. Chino City had established the “Guidelines for Installation of Renewable Energy Power Generation Facilities in Chino City” in September 2014, but they are not legally enforceable, and this time the business site is in Suwa City. Therefore, it is difficult for the government to respond. In this case, the prefecture’s environmental assessment system actually plays the role of a system that decides whether or not to carry out the project.

The second is the importance of the process of continuous activity of residents’ groups, expansion of networks, and increasing influence.

“Calm withdrawal” in Fujimi Town

In Fujimi Town, Nagano Prefecture, a 24 MW solar power generation project on the land owned by a local autonomous region at the foot of Mt. Yatsugatake, has been underway by company B from Tokyo since the middle of 2013. The local residents’ group was concerned about sediment-related disasters, the impact on groundwater, and the impact on the landscape and submitted a request for regulation by ordinance to the mayor.

They also requested businesses to hold briefing sessions for residents for all townspeople.

In October 2015, Fujimi Town formulated the “Guidelines for the Installation of Renewable Energy Power Generation Facilities” because of the increasing number of conflicts in the town, including small-scale projects. These guidelines target facilities of 10 kW or more and stipulate advance submission and adjustment of plans, holding briefing sessions for residents, reduction of environmental impact, etc., but they are not legally binding.

As a result, company B canceled the plan in January 2017. Even though it continued discussing with the local residents, it did not obtain the consent of the surrounding autonomous regions based on the town’s environmental conservation ordinance. Such withdrawals are rare in large-scale projects with dozens of MW. There are two lessons derived from this case.

First, the deciding factor for the withdrawal of the project was the Environmental Conservation Ordinance, which reflects the history of the town and its inhabitants. Since the ordinance was established in 1978 (revised in 1988), it is clear that it was not created for mega-solar development. However, the existence of this ordinance is proof that autonomy has been emphasized against externally-led development.

The second is the attitude of the business operator. The business operator held discussions to gain the understanding of neighboring residents, and even if the discussions followed parallel lines, there were no violations of laws and regulations or unreasonable continuation of development. It may be unpleasant for the resident group who started the movement, but we think that such a case should be widely shared as a “calm withdrawal”. On the flip side, it also means that forcible land development is taking place in various parts of Japan.

Institutional response of Nagano Prefecture

In Nagano Prefecture, there are many mega-solar projects in forest areas, and regional conflicts have become apparent from early on.

Nagano Prefecture, led by the Environment and Energy Division, began the discussions between the prefecture and the municipalities at an early stage for regional conflicts and devised countermeasures along with related prefectural departments.

In particular, since May 2015, through the examination at the “liaison conference on the proper promotion of photovoltaic power generation” in the prefecture and the municipalities, comprehensive measures have been taken.

Nagano Prefecture formulated the “Municipal Response Manual for Proper Promotion of Photovoltaic Power Generation-Promotion of Renewable Energy Business in Harmony with the Region-” and announced it in June 2016.

Furthermore, large-scale mega-solar development will be revised to be subject to the prefecture’s environmental assessment ordinance. For the mega-solar development of several MW scales, the prefecture presented a proposal for a regulation that includes advance notification and consensus building with residents. It also encourages businesses to conduct regional collaborative projects.

By combining these policies, they are not only responding to regional conflicts but also promoting desirable renewable energy projects that are regional-led or collaborative.

Two lessons can be derived from Nagano Prefecture’s comprehensive countermeasures.

First, through the formulation of the environmental energy strategy in 2013, the ideal method of renewable energy business was defined before the regional conflicts occurred, and comprehensive and prompt measures were examined.

Secondly, the division of roles between the prefecture and the municipalities was clarified and examined from the beginning. The large-scale mega-solar developments are handled by the prefecture, and small-scale developments are handled by the municipalities according to individual circumstances. For that purpose, the prefecture provides generous support. Such a policy response of Nagano Prefecture gives valuable suggestions to other local governments.

Whereabouts of regional conflicts in Ito City

In Ito City, Shizuoka Prefecture, Company C was proceeding with a mega-solar project exceeding 40 MW near the village area.

From around April 2007, local residents and fishermen raised concerns about the deterioration of the landscape and the aquatic environment. Mayor Ono, who was elected in May 2007, also requested a major review of the plan.

The resident group has been active in collecting signatures against the plan and they have submitted them to the city and the prefecture.

On July 4, 2007, the Ito City Council unanimously passed a resolution against the development activities associated with the construction of solar power plants.

Subsequently, Ito City formulated the “Ordinance on Harmony between the Beautiful Landscape of Ito City and the Solar Power Generation Facility Installation Project” and it was enforced in June 2008.

In this case, whether or not the construction is started before the enforcement of the ordinance determines whether or not the plan of Company C is subject to the ordinance.

Company C claims that it has obtained permission from the Housing Land Development Regulation Law and started construction as of May.

However, the city has expressed its opinion that the regulation ordinance will be applied to the plan because the construction has not started yet as of June as the residents’ group pointed out the inadequacy of the plan.

On the other hand, although the Governor of Shizuoka Prefecture expressed concern about the plan, he permitted the forest land development in July 2008 based on the report of the Prefectural Forest Council. The development was not subject to the environmental assessment because the area of construction was 45 ha.

Under these circumstances, on August 23, 2008, the residents’ group submitted a request to the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry to cancel the authorization of the business operator together with the prefectural assembly and members of the Diet. After that, the business operator gave an explanation to the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry.

There are three lessons that can be derived from this case.

First, as in the case of Suwa City and Chino City described above, it is easy for the institutional response of local governments to fall behind, and the situation can change dramatically depending on whether the ordinance is in time or not.

Second, the residents’ group, including experts, is extremely practical. The solid activities of the residents’ group, such as pointing out the incompleteness of the application documents of the business operator, have great influence.

Finally, the response of the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry. In the past, when local conflicts occurred, the residents often consulted with the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry online or by telephone, but the response was not officially announced.

The future of this case is still unclear, but it can be a touchstone that will have a significant impact on the operation of the revised FIT Act in the future.

Regional conflicts of small and medium-sized enterprises

Not only with a large-scale project such as dozens of MW, but also small and medium-sized businesses of several MW or hundreds of kW can be regional problems. We will refrain from detailing each specific case, but ultimately, regional conflicts are likely to occur in forests and hilly areas.

Regional conflicts can occur even at low voltage scales of less than 50 kW.

Some say that the solar power generation business in a clear space of a residential area does not match the scenery of the city, and there is a concern that the reflected light may be too glaring. In addition, if there are no legal defects, the government cannot deal with businesses, and they often start with dissatisfaction among the local residents.

Concerns about solar sharing

Solar sharing (continuous farming solar power generation), which aims to increase farmers’ income and the potential of solar power generation, is attracting attention. Solar sharing is a mechanism to introduce solar power generation on top of farming. Local conflicts can occur even with this solar sharing.

For example, there are concerns about landscape and disaster prevention. The landscape of the agricultural area may change, and the measure against typhoons is important due to the simple structure of solar panels.

In addition, if the number of farmers who engage in this practice increases because gaining income from selling electricity becomes the main purpose, it will give an unfavorable impression that solar power generation is even more unacceptable to society.

With regard to solar sharing, the number of projects accepted by the regional areas is expected to increase, led by organizations such as the Solar Sharing Promotion Federation.

Community-led renewable energy business that enhances local acceptability

Fig. 3 The completion ceremony of the Tomioka Reconstruction Solar Takatsuto / Shimizumae Solar Power Plant

Fig. 4 Public-private collaboration solar power generation of the Niigata city Kurosaki civic hall

Fukushima / Tomioka Reconstruction Solar

In contrast to the case shown in the previous section, many community-led, decentralized, and regionally highly acceptable solar power generation projects have been launched.

These are initiatives centered on citizens and local businesses who are interested in renewable energy, and are also called “community power projects”.

In Tomioka Town, Fukushima Prefecture “The Tomioka Reconstruction Solar Takatsuto / Shimizumae Solar Power Plant (32MW)” was completed in 2018 and started selling electricity.

ISEP has provided full support in response to the desire of local residents to promote renewable energy in the land contaminated by the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant accident. In this project, local residents are the owners, and citizens from all over the country are also participating through investment by utilizing the citizen investment method.

Moreover, it is under consideration that a part of the profits of this project is used for social activities for regional reconstruction. In this way, the energy and the regional reconstruction are closely linked. Although it is a huge project with an area of 35 ha, it is currently underway as a project rooted in the region.

Niigata public-private collaboration solar power generation business of “Orate”

In Niigata City, the government and citizens have collaborated to develop a decentralized solar power generation business. “Orate” a private business entity based on the Niigata Citizens’ Energy Council has been established, and has signed agreements with Niigata City and surrounding local governments, focusing on businesses that utilize the roofs of administrative facilities and businesses on privately owned land. It operates more than 40 solar power generation businesses of around 50 kW. “Orate” means “us” in the Nigata dialect and it symbolizes the involvement of the many actors in this project.

In this project, the scale of each power plant is small, so conflicts are unlikely to occur in the first place, but continuous cooperation between the government and citizens is extremely important from the perspective of gaining credibility in the region.

Spreading local energy

Many other community-led solar power generation businesses have been launched as well. AiPOWER was founded by The president of the Yamatogawa sake brewer in the Aizu region of Fukushima prefecture with local people to promote renewable energy in the wake of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant accident. They utilized the citizen investment and installed a 1 MW scale solar power plant. Tokushima Regional Energy is developing a donation-type “Community Happy Solar”.

In these areas, local people have come to terms with the photovoltaic power generation business and it provides important suggestions from the aspect of the business model when considering the relationship between renewable energy and regional areas.

Fig. 5 The solar power plant of AiPOWER

Utilizing the lessons derived

Lessons derived from the local conflict cases

Here are five main lessons derived from local conflict cases of photovoltaic power generation towards governments, businesses, and residents’ groups.

First, it is of utmost importance for the local government to establish an appropriate method of renewable energy business. If local governments make clear rules in ordinances according to the revised FIT Act, it will lead to the prevention of regional conflicts. On this occasion, even if the restraint area is first defined to prevent overdevelopment, it would be desirable if the local governments could consider and support the recommended renewable energy business that should be promoted in the future.

Second, since local conflicts in solar power generation can occur anywhere, there is a high possibility that even if the local governments establish an ordinance after the fact, it will not be in time. That is the issue in Ito City. Furthermore, regional conflicts do not occur in the same way and it does not only depend on the scale or whether it is an external development type. In that sense, it is important to pay attention to the 850 local governments that answered that “conflicts have not occurred so far” and “conflicts are unlikely to occur in the future”, or “no information”.

Third, it is important for businesses to always have “calm withdrawal” as an option depending on the situation. It is only natural to carry out business development in accordance with the rules and the long-term reputation of the company is key.

However, in both the communication with the community and the environmental assessment, the situation is that “honest people embarrass themselves (the more carefully they do, the more costly it becomes)”. The institutional environment should be changed in such a way that honest people benefit.

Fourth, it is effective for residents’ groups to solve regional conflicts by responding from both network and practical aspects. In each case, the resident groups are expanding their supporters with the support of experts and their ability to communicate through social and mass media. In addition, in Ito City, scrutiny by the residents’ group revealed a mistake by the business operator, and it turned the tide of whether or not the business was subject to the ordinance. Such cases were also seen in the efforts to tackle pollution, dams, and nuclear power problems, reminding us of the idea of ”citizen science”.

Fifth, the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry should clarify the procedures for guidance and revocation of certification to some extent for the problematic photovoltaic power generation projects and expand the response system.

To reduce local conflicts

In the future, in order to reduce regional conflicts in the photovoltaic power generation business, it will be necessary to take measures from the institutional, practical, and social aspects.

Regarding the institutional perspective, a zoning method that indicates suitable areas and restricted areas for renewable energy use from the physical, social, and environmental conditions can be one of the effective solutions. However, the land usage regulations vary in Japan, and it is difficult to achieve zoning at the national level in an early stage.

For future discussions, it will be important to refer to the comprehensive and consistent location control by the federal, the states, and the municipalities as in Germany (for regional zoning, see the Ichikawa paper in this special edition. See also the Chiba paper for city planning in Germany).

In addition, it is considered that there are many problems from the viewpoint of administrative practice in the framework of the current revised FIT Act, the disposition of which is based on other laws and ordinances. Therefore, it would be better to amend the FIT Act or enact another regulation to have well-ordered businesses.

In practice, it is crucial to increase the number of community-led projects that are acceptable in the regional areas, such as the example of local energy. Increasing community-based projects is also important, even if it is an external development type business. The consensus-building procedures should be performed more carefully and sufficiently to bring social benefits to the areas.

It is also necessary to increase social acceptance for the creation of broader renewable energy and sustainable society. The initiatives of Germany, “Specialized Center for Energy Conversion and Nature Conservation”, are very helpful in increasing social acceptance.

For example, the FAQ site operated by the center covers themes such as wind power generation and its impact on wild birds, which are common in Germany. And it widely shares concise answers and detailed discussions by multiple experts. In addition, it may generate a mediation of discussions and arbitration of conflicts on site. How to set up such an organization in Japan is of great significance.

Comprehensive implementation of these institutional, practical, and social measures is the key to reducing conflicts and increasing sustainable renewable energy businesses.

—

Text: Noriaki Yamashita (Institute for Sustainable Energy Policies)

オリジナル掲載:岩波書店『科学』2018年10月号